Contents: Early Establishments | Southeast Oktibbeha Community Schools

Foundations

Ebenezer Community Church school

Early Establishments

From Enslaved to Educator

Upon the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, the newly freed Blacks demanded for universal schooling and began to find ways to teach themselves in what came to be known as “native schools.” By 1866, John W. Alvord, the national superintendent of schools for the Freedmen’s Bureau, estimated 500 of these schools were extant. Noticing the burgeoning demand for education, Major General Nathaniel P. Banks helped establish the “most thorough … systems for educating freedmen in his Department of Gulf,” which consisted of 60 different schools in Mississippi, Louisiana, Alabama, and Texas by 1864. A year later, Lincoln’s Fredmen’s Bureau took control of the school system that now consisted of 126 schools and 19,000 students (John W. Blassingame, “The Union Army as an Educational Institution for Negroes”; Anderson, Education of Blacks in the South, 1860-1935).

By 1867, the Freedmen’s Bureau and Northern relgious societies helped build 61 Black schools had been built in Mississippi, educating a total of 4,500 students (Bolton, The Hardest Deal of All). Although White supremacy continued to plague southern Blacks, between 1860-1880, those who were formerly enslaved made immense strides to attaining proper education on legal, instituitional, and moral grounds; moreover, their efforts cultivated a rich foundation for the educational reforms in the 1880s-1890s and into the early part of the 20th century to ensue (Anderson, Education of Blacks).

Booker T. Washington, a former slave himself, established the Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute in 1881. Soon thereafter, the endorsement from Samual Chapman Armstrong, a Union general during the Civil War, brought in the “Hampton-Tuskegee Idea,” a pedagogy focused on the training of teachers, not agriculture. Normal school student’s tended to be older and more economically disadvantaged individuals who sought two years of professional education and teacher preparation courses so they could attain their common school teaching certificate. However, Armstrong, and therefore Washington, desired to instill the “dignity of labor” into Black students, something that made manual labor the criterion for educational excellence. In other words, Armstrong feared highly educated Blacks and advocated for teaching Black students a low-grade material and to “love” labor rather than teaching higher trade and/or technical skills. Although Armstrong’s ideology barred students from higher education and skills, the growth in Black educators was a major stepping stone to propogating education for southern Blacks (Anderson, Education of Blacks).

By 1900, Mississippi saw roughly 39% of children between the ages 5-14 attending school. The low number can be accreditted to many factors, including the shortage of teachers and child labor. Even though the Hampton-Tuskegee Model produced 2,500 Black educators a year, the yearly demand sat at 7,000. Simultaneously, about 40% of Black children, boys and girls, were required to work, a statistical percentage that was only 15% for White children.

While extensive efforts to establish rural schoolhouses across the South began in 1913 with Julius Rosenwald, Mississippi did not have a single public high school for Blacks by 1916. Consequently, 95-97% of the southern Black population was not enrolled in public instituitions. By 1924, little improvement was seen, as only 3 Black public schools has been built. These were located in Vicksburg, Yazoo City, and Mount Bayou. This disparity caught the eyes of many philanthropists, Rosenwald being one. Rosenwald attended a conference in Gulfport, Mississippi discussing southern education made a conscious effort to discuss the development of Black public high schools. Between 1927-1928, Oktibbeha’s Pleasant Grove was erected with the help of Rosenwald.

Southeast Oktibbeha Community Schools

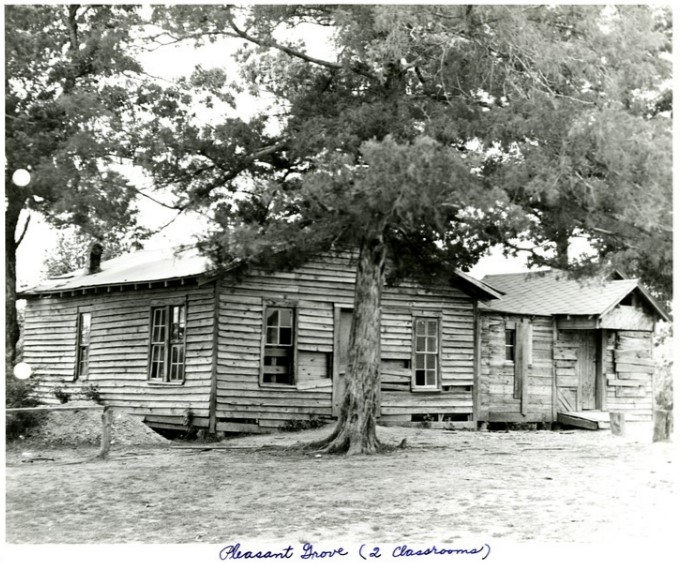

Pleseant Grove

Pleasant Grove was a community school that was built between 1927-1928 on a 2 acre body of land adjacent to Pleasant Grove Baptist Church, replacing “New Prospect,” a school that had been around since at least 1900. For over 30 years, Pleasant Grove served as the High School for other communities in southeast Oktibbeha county, such as Zion Franklin, Pine Grove, St. Matthew, Turnpike, Mt. Olivet, McGee, Austin, and Bethel, which only educated students until 8th grade. Managed by local trustees and a supervisor who oversaw all community church schools, Pleasant Grove resided justa few miles from where B.L. Moor would be constructed years later.

In total, the estimated cost of the Pleasant Grove project was $200,000, something Rosenwald and parents contributed to equally. The building contained five classrooms, an auditorium that served as two classrooms, and ten teachers. Additionally, state recordsclaim the building had electricity, coal stoves, pit toilets, drinking fountains, a deep well, and an electric pump. While attending the school, male students were responsible for janitorial services, as well as cutting and kindling the fire to maintain sustainable temperatures.

Although the building had improved through the help of Rosenwald and local families, the struggle to find teachers remained, as the final Pleasant Grove valedictorian Shleby Jennings Scotts recalled there being “more than 50 pupils in my class.”

Extracurriculars

Pleasant Grove’s extracurricular activities included choir and basketball. Both of which were successful, as choir director Mrs. Hilliard was noted for winning competitions, and both the girl’s and boy’s teams had a winning percentage above .500.

Outside of these two organized activities, students could be seen playing marbles underneath the school where they had dug holes, or basketball on the grass nearby. The school desired a football team and Mississippi State University donated equipment to do so, but the inability to find a suitable location to practice and play suspended that possibility until the late 1960s.

Other Community Schools Prior to 1960

Austin was affiliated with the Church of Christ denomination in the Sessums community. According to MDAH, it served as an eighth grade center with one teacher, but former students recall both Ms. Emma Conley and Ms. Hattie Spencer teaching at the location.

Bethel, located on Bethel M.B. Church property, was also an eighth-grade center with one story frame structure with a metal roof containing two classrooms and two teachers. Appliances included electricity, a coal stove, outdoor toilets, and good furniture but lacked accessibility to water. Bethel served as a community center for functions such as cake walks, feasts, and educational fundraisers for the community.

Chapel Hill School was an eigth grade center on church property of modern day Harris Road in Starkville, Mississippi. This one story, one classroom building possessed electricity, an outdoor toilet, and a coal stove but no water.

McGee was located on 10 acres of land near the current Pike and Spruill intersection in southern Starkville, Mississippi. The eighth grade, one story, one classroom structure had a metal roof with outdoor toilets, and a coal stove. It is unknown whether the school had a community church affiliation, but the teachers noted were Mrs. Willie Adams, her aunts Idella Minor, and Willie Dora Dickerson.

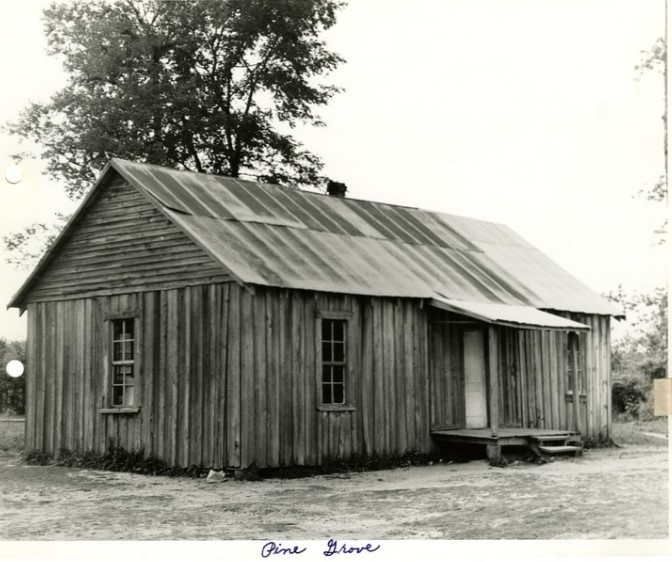

Pine Grove was an eighth grade center built across from Pine Grove Baptist Church on Bluff Lake Road road, near the Bluff Lake reservoir. The one story, one classroom structure had a metal roof. The last two teachers noted were Mrs. Martha Bibbs and Ms. Thelma Roberson, and the common last names that attended this school were Rice, Ellis, McGee, Mobley, Nicholas, Brown, Edward, Moore, Spearmon, and Gillespie. And despite the various last names listed, Pine Grove served a small community; many students were commuting from other parts of the county and were not immediately part of the community.

True Vine, the only other Rosenwald school in southeast Oktibbeha, was located west of Artesia on modern day Artesia Road. The two teachers were Mr. Glenn Elliot and Mrs. Elsie Mosley. Turnpike was an eighth grade center with one story, two classrooms, and a metal roof on the modern day dead end of Pike Road in southern Starkville, Mississippi; the land belonged to Zion Franklin United Methodist Church. It had electricity, good furniture, coal stoves, outdoor toilets, and watern from a cistern. Ms. Thelma Robinson, who also taught at Pine Grove, taught at the location. St. Matthew was located on church property near Artesia, Mississippi. It was also one story, but only had one classroom and tin roof. Before conditions became too poor to continue operation, there was electricity, a coal stove, and outdoor toilets. St. Matthews’s two teachers were Mrs. Beatrice Jerry and Mrs. Idella Minor.