Contents: Julius Rosenwald's Impact | Commitment of Oktibbeha Co. Residents

Educational Growth

1913-1950

Julius Rosenwald’s Impact

Prior to 1960, several small, community schools educated Black students of all ages in southeast Oktibbeha county. These one-to-two room community church schools included Pleasant Grove, St. Matthews, Austin, Truevine, Pine Grove, Zion Franklin, Mt. Olivet, and Bethel. Various church schools in Oktibbeha county, including Pleasant Grove and Truevine, were built with the help of Julius Rosenwald, a Chicago businessman and philanthropist who sympathized with the injustices Black Americans faced. These schools were also affiliated with local churches that provided the appropriate resources and land for the construction of the schoolhouses.

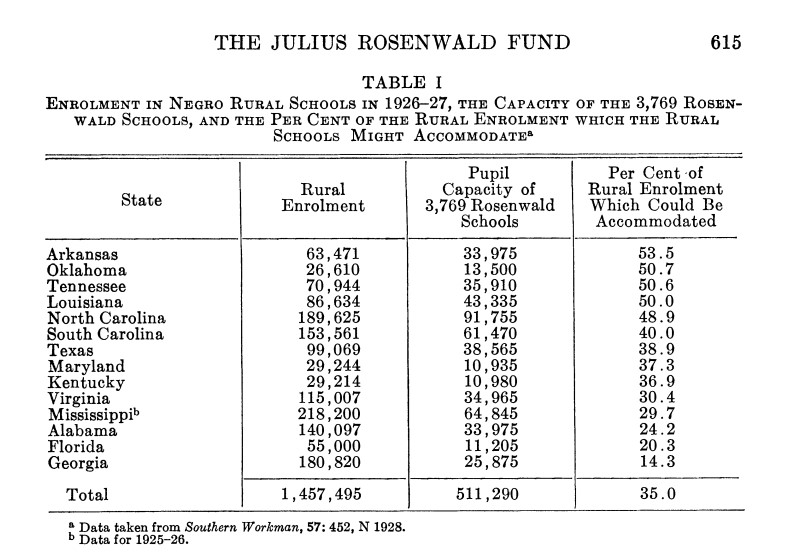

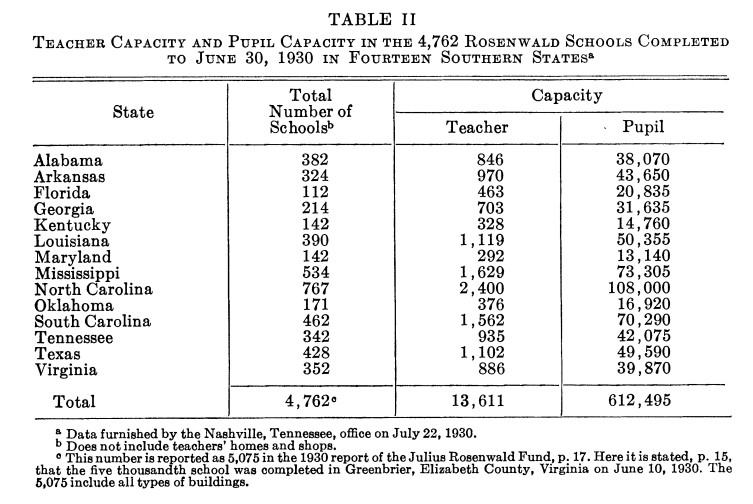

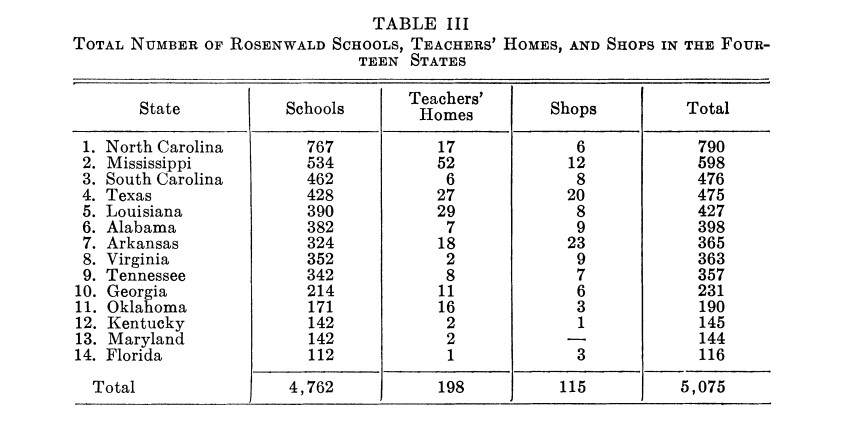

Rosenwald, alongside Booker T. Washington, found providing schools in the rural south would be one way of giving Blacks a fair chance at equal citizenship, something that would be for the “well-being of mankind,” as his charter stated. After the first Rosenwald schoolhouse was completed in Alabama in 1913, Rosenwald went on to spend $4.8 million to construct Rosenwald schools across 14 of the 16 southern states by 1932 when his and Washington’s “Plan for Erection of Rural Schoolhouses” ended. (For more, see Hoffschwelle, Wilson, and McCormick’s “The Julius Rosenwald Fund”).

Commitment of Oktibbeha Co. Residents

Rosenwald was not alone in his monetary contributions, as Black parents consistently illustrated their committment in providing education for their children by matching Rosenwald’s contributions to build, maintain, and provide for these schools. In fact, southern Blacks of the 14 southern states donated $90,848.25 in 1930-1931, and in 1932-33, amidst the Great Depression, Black Mississippians raised $1,965 (Anderson, Education of Blacks in the South, 1860-1935). These donations cannot be understated. Studies show only rural Blacks who were primarily tenants and sharecroppers could earn beyond what was needed for bare necessities, as the average annual income for a Black family in 1934 was $105.43 (Anderson). In addition to their monetary donations, rural Black communities donated their land, materials, time, and labor to construct these schools, hoping to gain educational equity amid numerous hindrances such as segregation, disenfranchisement, and White supremacy.

One major hindrance resided in Mississippi legislation, for despite Black families paying local taxes for schools their children could not attend, the law prohibited the board of education from expending any funds on construction projects unless the county had its own tax levy for building projects, and White schools had precedence due to racial discrimimation; however, in 1930, Mississippi state officials successfully advocated for a school law revision, allowing local taxes to be allocated for African American projects. Undoubtledly, progress was being made, albeit slowly, as Allen M.S. Landfair, a former student and teacher of B.L. Moor, expressed the same issue thirty years later saying, “it was rumored that students at the county schools were inferior in learning to those of the city schools, but what most people didn’t understand that the major difference was in the taxes, not in the instructors or learning capabilities of the students.” But even before the new legislation of 1930, Black contributions were evident, as one of the three public high schools for Blacks at the time, Mount Bayou, was built solely from Black contributions in 1924—$115,000 (Anderson; Hoffschwelle; Diette, “A Retrospective Analysis of the Racial Composition of Schools”). Time after time, Black Mississippians displayed resilience and fortitude to improve their educational opportunities.

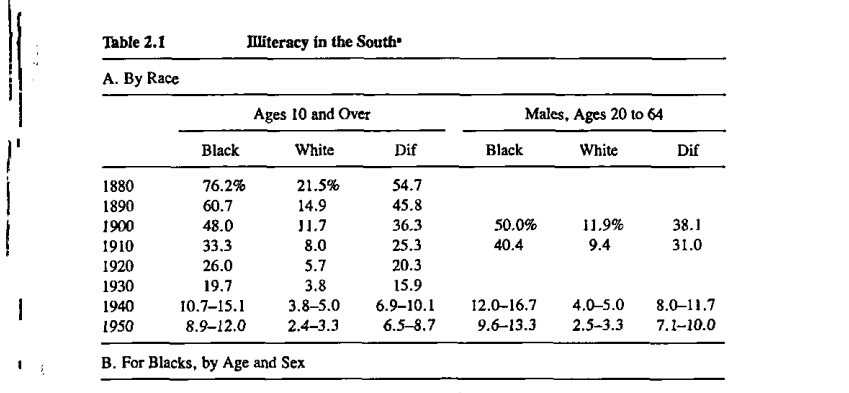

By 1930, the monetary contributions of Rosenwald and Black families had already made an impact on Black education in Mississippi, as they had extended the average length of their school years by 3.9 months from 1915 and dropped their illiteracy rate from 76% in 1880 to 19.7% and to 8.9% by 1950 (Margo, Race and Schooling in the South, 1880-1950). Although Rosenwald schools had increased their terms by nearly 4 months, schools such as southeast Oktibbeha’s Pleasant Grove high school still had to cut the year short due to students having to help provide food and income for the families.

Despite these challenges, local educators in these community schools made attending school possible, before and after Rosenwald’s involvement. D.R. “Dock” Rives, whose father was enslaved and forbidden to learn how to read and write, served southeast Oktibbeha as a local educator. Dock, just one generation after the Emancipation Proclamation and the Civil War, went on to educate Black youth from 1900-1950 at McGee, Bethel, Turnpike, and others; furthermore, Dock’s grandaughter, Lillie Rives Ellis also educated students at community schools throughout the 50s, creating a family tradition of educators. Educators who had overwhelming odds stacked against them, like Mr. Rives and Mrs. Ellis, are the ones who made such educational improvements throughout the 20th century possible.

By 1932, the year of Rosenwald’s death, he had built 4,762 schools across the 14 southern states, 557 of them being in Mississippi. In addition to schools, Rosenwald aided trasnportation by providing bus services in rural areas like southeast Oktibbeha county. But Rosenwald’s death did not deter Black educations advancement in Mississippi, as they continued to thrive with improvement and local involvement. For example, only 32% of Black teachers in Greensboro held a college degree in 1932, but by 1952, all Black teachers held a college degree, with 65% earning a Master’s degree. Furthermore, Black colleges doubled their enrollement in 1940s, increasing their income from $8 million in 1930 to $38 million in 1947 (Klarman, “Brown, Racial Change, and the Civil Rights Movement,” p. 66). The Oktibbeha community’s efforts, paired with the help from Rosenwald, made great strides for southern Black education, but there were still vast improvements to be made, as 1,428 of Mississippi’s 3,737 public schools for Blacks still met in private buildings such as barns, lodges, tenant cabins, and churches in 1934, something that would remain unchanged until the Brown v Board ruling in 1954 (Hoffschwelle, 2008).